Its never to early to be thinking about 2010 and a bruising Senate primary in Pennsylvania has the potential of giving Democrats the magic 60 seats they need to end minority filibusters. Like in 2004, Arlen Specter finds himself challenged from his right flank by Pat Toomey, former House member of the 15th district and now president of the anti-tax, fiscally conservative think tank Club for Growth. While Specter clearly enjoys his position as the fulcrum of the current Senate—one of a small cadre of moderate Republicans who decide what legislation will go forward (Yes on stimulus; No on card check)—he has opened himself up once again to Toomey’s claim that Specter is out of step with Keystone State Republicans. While Specter might have no problem winning the general election next year, he may not get that far given current trends in the state and national GOP. If we look back to 2004 and move forward we can see some clear signs of danger for Specter.

Its never to early to be thinking about 2010 and a bruising Senate primary in Pennsylvania has the potential of giving Democrats the magic 60 seats they need to end minority filibusters. Like in 2004, Arlen Specter finds himself challenged from his right flank by Pat Toomey, former House member of the 15th district and now president of the anti-tax, fiscally conservative think tank Club for Growth. While Specter clearly enjoys his position as the fulcrum of the current Senate—one of a small cadre of moderate Republicans who decide what legislation will go forward (Yes on stimulus; No on card check)—he has opened himself up once again to Toomey’s claim that Specter is out of step with Keystone State Republicans. While Specter might have no problem winning the general election next year, he may not get that far given current trends in the state and national GOP. If we look back to 2004 and move forward we can see some clear signs of danger for Specter. So, going into next year’s contest might Specter simply try and repeat his 2004 performance? While in theory this might be desirable, changes over the past several years make following the old playbook precarious. If we look at more recent elections it becomes apparent that much of Specter’s base of support has been defecting from the Republican fold. It must be noted that Pennsylvania primaries are open only to registered partisans. Thus, Specter cannot rely on independents or Democratic voters to carry him to victory. Only registered Republicans will determine his fate, despite his recent attempts to get state leaders to change the primary rules. If we compare party registration figures for 2004 and 2008 we see problems for Specter. I’ve isolated those counties that provided Specter’s best performance to illustrate this point. As we can see, over the past four years Philadelphia, Montgomery, Delaware, Bucks, and Chester Counties have shed over 124,000 registered Republicans. Democrats, meanwhile, have gained over 220,000 registrants. Whether these Republican losses have become independents or Democrats is irrelevant for the primary. The important fact is that they are now out of that electorate and out of Specter’s reach unless he can get them to re-register, a daunting process in the midst of a campaign.

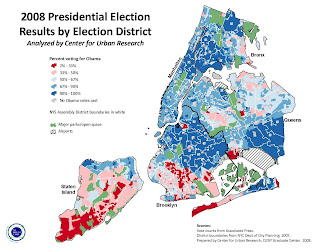

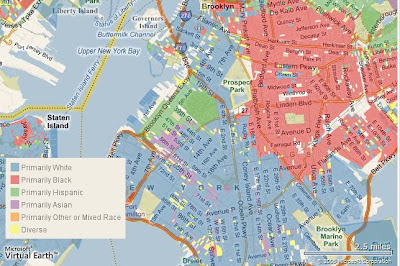

So, going into next year’s contest might Specter simply try and repeat his 2004 performance? While in theory this might be desirable, changes over the past several years make following the old playbook precarious. If we look at more recent elections it becomes apparent that much of Specter’s base of support has been defecting from the Republican fold. It must be noted that Pennsylvania primaries are open only to registered partisans. Thus, Specter cannot rely on independents or Democratic voters to carry him to victory. Only registered Republicans will determine his fate, despite his recent attempts to get state leaders to change the primary rules. If we compare party registration figures for 2004 and 2008 we see problems for Specter. I’ve isolated those counties that provided Specter’s best performance to illustrate this point. As we can see, over the past four years Philadelphia, Montgomery, Delaware, Bucks, and Chester Counties have shed over 124,000 registered Republicans. Democrats, meanwhile, have gained over 220,000 registrants. Whether these Republican losses have become independents or Democrats is irrelevant for the primary. The important fact is that they are now out of that electorate and out of Specter’s reach unless he can get them to re-register, a daunting process in the midst of a campaign. To get a sense of how these changes in the Philly area have been changing the tenor of the state’s politics, its useful to compare the presidential vote in 2004 and 2008 (numbers are provided in the spreadsheet). As shown in the chart at left, Barack Obama performed significantly better than John Kerry in all five of these key counties. This is especially notable in the suburbs. Thus, whereas Kerry’s statewide victory was about 144,000 votes, Obama took the state by 620,000 votes. When Pennsylvania was called so quickly on election night it was because of the sizable shift to the left taken by this region.

To get a sense of how these changes in the Philly area have been changing the tenor of the state’s politics, its useful to compare the presidential vote in 2004 and 2008 (numbers are provided in the spreadsheet). As shown in the chart at left, Barack Obama performed significantly better than John Kerry in all five of these key counties. This is especially notable in the suburbs. Thus, whereas Kerry’s statewide victory was about 144,000 votes, Obama took the state by 620,000 votes. When Pennsylvania was called so quickly on election night it was because of the sizable shift to the left taken by this region.So, as Specter contemplates how to approach his looming primary fight, he’s confronted with the fact that the part of the state that has been his base of support for the past three plus decades is in the process of a steady move to the left. Those voters who, while moderate, were willing to stay registered as Republicans have been fleeing the GOP. A more conservative Republican electorate is clearly much more advantageous to Toomey. What Specter needs to hope for is that Republican voters see the virtue in having him in his current position—namely that of a dealmaker in the Senate. Toomey, while more in line with these voters' ideology, won’t have the institutional sway that Specter does. Is an influential, yet Republican-lite Specter more useful than a more pure, but marginalized Toomey? Specter will also hope that Toomey has lost the connection to the state that he had while representing it in Congress. The years spent running an outfit like the Club for Growth have necessarily removed him from the day to day workings of the state. He may thus be hampered in his attempt to swoop back in and knock off someone who has been courting and serving constituents for years.

Another option for Specter that has been discussed would be to run as an independent. Theoretically, he could decide to do this either before or after the primary. Given how much the landscape could change over the next year, its difficult to speculate on which option, if either, would be more desirable. A big unknown so far is what the Democratic field will look like. If Specter wants advice about how to go about this, though, he doesn’t need to go far--just a few steps across the Senate floor. Just three years ago, one of his colleagues went this route—Joe Lieberman. In many ways the Democratic Party’s version of Arlen Specter, Lieberman was challenged from his flank. Defeated in the Democratic primary by Ned Lamont, Lieberman regrouped and was elected as an independent. Thus, while we don't know how Senator Specter will ultimately play the hand he's been dealt, at this point there seem to be troubling signs ahead.