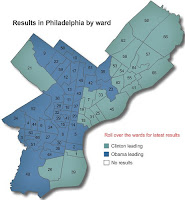

As the debate continues about the state of the Obama/Clinton contest and how it will affect the Democratic nominee’s chances in November, I thought it might be helpful to take a bit of a historical look at this issue. With all sorts of pundits, journalists, and Democratic activists in a tizzy over this question, taking a step back is clearly in order.

As I mentioned in my post on realignment, Walter Dean Burnham identified a process, rapidly unfolding by the 1960’s, of party “decomposition.” What he meant by this was that the party, as organization, was able to exert less and less control over the process by which party nominees were chosen. With the advent of the primary system the nomination process, while “democratized,” was also more subject to unpredictable and uncontrollable twists and turns. Candidates themselves became increasingly in control of the process and decisions about when to enter and when to exit the race were largely theirs to make. We see the manifestation of this today in the Democratic race.

This got me thinking about those nomination fights, for both parties, that have been the most contentious in the years since Burnham identified this process. Did these contentious nomination processes doom the nominee in the fall? Might there be other explanations for that party’s failure to capture the presidency?

While all nomination fights have some degree of conflict—indeed that’s what a nomination process is premised on—some have been more contentious and drawn out than others. I’ve identified four that seem to be the most cited as damaging to their party:

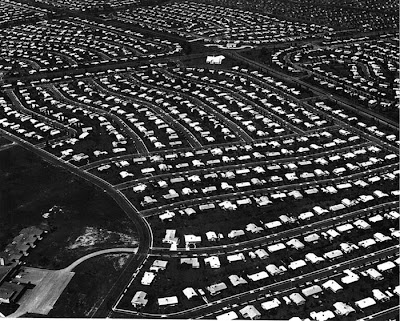

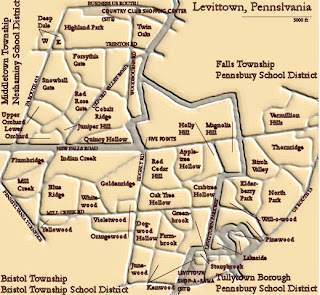

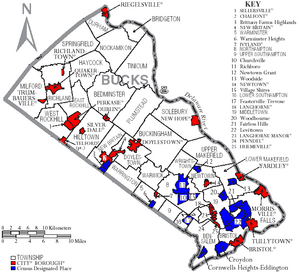

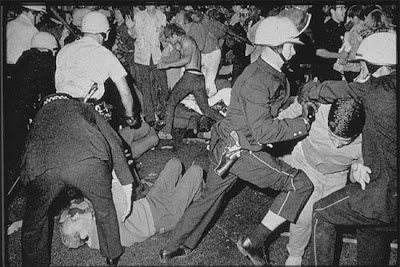

1968 Democrats. Here we have the classic example of a party in chaos and disarray. After President Johnson is embarrassed in the New Hampshire primary by Senator Eugene McCarthy, LBJ decides not to seek re-election. We see McCarthy continue, soon joined by Bobby Kennedy and the incumbent Vice President Hubert Humphrey. After the assassination of RFK, the party limps to the disastrous Chicago convention and awards the nomination to Humphrey.

1976 Republicans. President Ford, never elected Vice President or President due to the resignations of both Spiro Agnew and Richard Nixon, is seeking election in his own right. In the process he is challenged from the right by former California Governor Ronald Reagan. Reagan wins some primaries but drops out at the party convention in Kansas City.

1980 Democrats. President Jimmy Carter, in the midst of the Iranian hostage crisis, is challenged by Senator Edward Kennedy. Carter, despite capturing the White House for the Democrats in the wake of Watergate, is unpopular nationwide and within the Democratic Congress. Sensing the last chance at restoring Camelot, Kennedy jumps in the race and manages to win some contests but doesn’t come close to winning the nomination. Nonetheless, he doesn’t formally drop out until the convention in New York.

1992 Republicans. This case was probably the least contentious but still produced some surprises. Coming out of the Gulf War, George Bush’s popularity skyrockets, forcing many prominent Democrats to opt out of challenging him. As the economy begins to sour, commentator and former Nixon speechwriter

Pat Buchanan mounts a populist challenge to Bush for the Republican nomination. While the outcome of the nomination was never really in doubt, Buchanan’s challenge did signal difficulties ahead, both at the disastrous convention in New Orleans, and afterwards.

So what can we say about these cases? The first thing that we would note is that in all four cases the nominee eventually lost the general election in November. The 1968 and 1976 general elections were extremely close, 1980 and 1992 less so. Thus, a fractious nominating process would seem to bring bad tidings on a party.

But wait. Might we have the arrow of causality backwards? Rather than a party being weakened by a tough nomination fight, might that fight be the consequence of an already weakened party? Here, there seems to be compelling evidence.

One thing we would note about these contentious fights is that in all four cases it was the party in power that went through the wrenching nomination. As presidents’ terms progress, we tend to see a decline in their popularity, the fracturing of their original electoral coalition, and their tendency to be captured by events. With Humphrey in ’68, his inability to disassociate himself with LBJ’s Vietnam policy was an albatross he couldn’t shake. Ford in ’76 found himself bearing the brunt of voters’ Watergate rage, surely compounded by his pardon of Nixon. Carter in 1980, as mentioned, had the Iran hostage crisis, plus the general “malaise” of inflation to grapple with. Finally, Bush in ’92 had declining economic fortunes on his watch. Thus, while we normally think of incumbents as having tremendous advantages, a faltering presidency can be deadly, whether the incumbent is on the ticket in November or not.

A second thing to note about these election years is that in three of them—’68, ’80, and ’92 you had a credible third party candidate enter the race and perform well in November. George Wallace captured 13% of the vote, and five states, in 1968. Republican House member, turned independent candidate, John Anderson received 7% of the vote in 1980. Ross Perot in 1992 got 19%. Furthermore, in looking at the origins of these candidacies and the source of their support, we can see them essentially as spin-offs or breakaways from one of the major parties. Wallace had been elected as a Democrat, had sought the Democratic nomination before and would seek it again in the future. Anderson, as mentioned, was a Republican House member and seemed to tap into the liberal wing of the Republican electorate scared off by Reagan’s conservatism. Some of these voters may have flocked to Carter (although they wouldn't have been enough to save Carter's presidency). Finally, while never a Republican office holder, an examination of the Perot vote suggests he took more from the normal Republican electorate than from the Democratic side.

So, rather than dooming a party to failure, might a contentious nomination fight be a symptom of a much larger problem?

Looking at this year, then, what can we say? The first thing I would say is that it’s not at all clear that the Obama/Clinton contest has reached to level of rancor that these other races did. We’ll have to see how the next few months play out. Second, one thing working in the Democratic nominee’s favor, whoever it is, is that they are the party out of power right now. It is John McCain who will be occupying the role of Hubert Humphrey, to use the Vietnam/Iraq parallel as an example. Neither Obama nor Clinton has to defend the current administration. There will inevitably be a rallying behind the Democratic nominee—it’s easier, perhaps, to storm the castle than defend it. Finally, we don’t have a credible third party candidate this year to siphon off votes from the left. That will work to the Democratic nominee’s advantage. If we look at the fundamentals—Bush’s approval rating, perception of the economy, opinion of the war in Iraq, Democrats’ performance in the ’06 midterms, etc.—things seem to look good for the Dems.

So for those worrying about whether Clinton voters will support Obama or whether Obama voters will support Clinton, you need to settle down.